While the scientific peer review process has been in use for nearly two centuries now, it was neither as set in stone nor as robust as it is today. That change, which has given modern science much of the public trust on which it now relies, came as recently as the 1970s with the corporatisation of the scientific journal—no doubt in part because the corporations themselves wanted to strengthen their legitimacy and business model.

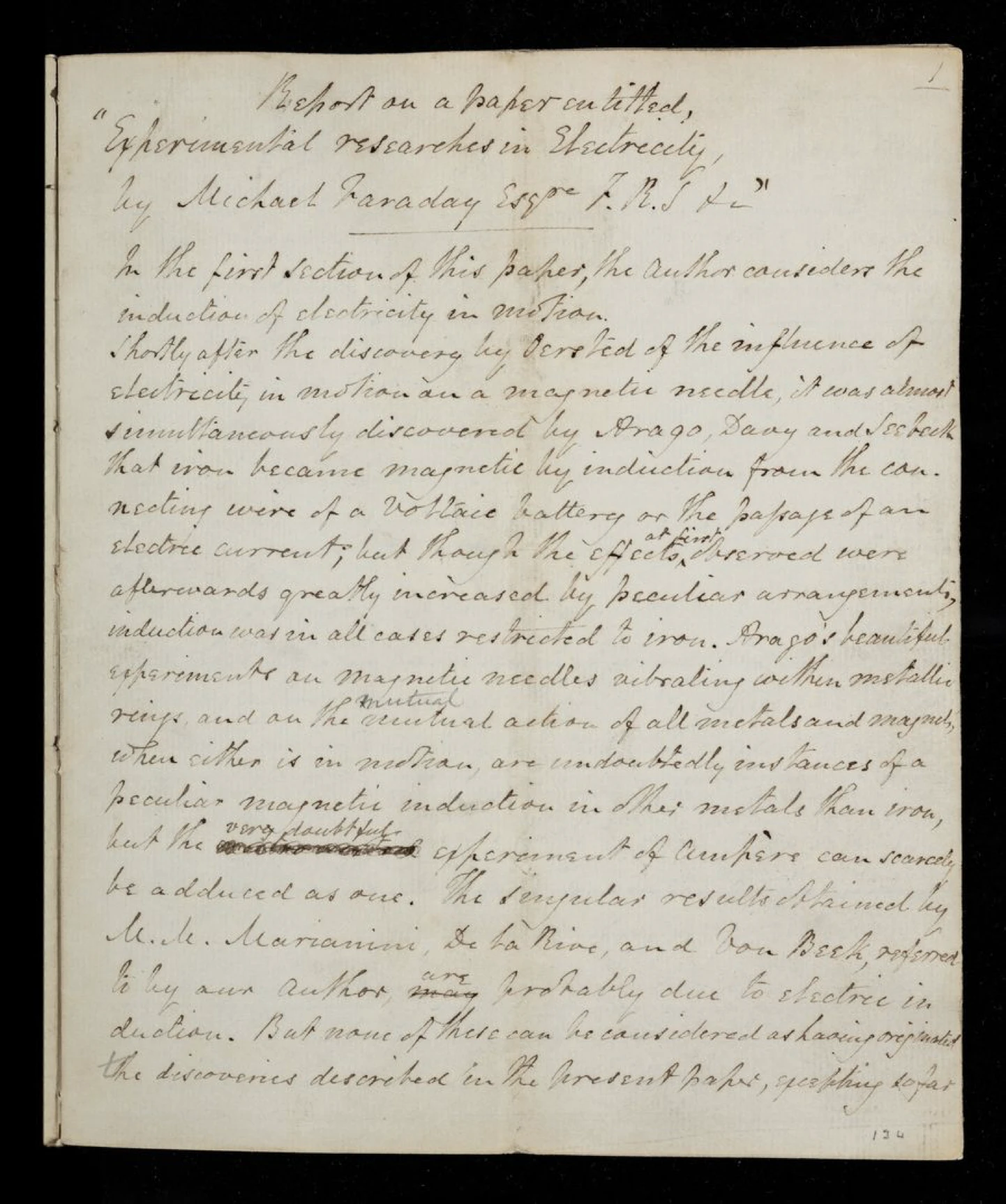

An early review on record is for a paper by Michael Faraday on ‘Experimental researches in electricity’ (pictured below) by Samuel Hunter Christie (who proposed the Wheatstone bridge) and John Bostock. The review carries no discussions or recommendations for editing, simply a 15-page summary of the reviewer’s understanding of the paper and a recommendation for publication. This was no earlier than the 1830s and the entire peer review process was informal. It was simply a matter of having a couple of others look at a paper before it was published to make sure things were not completely ridiculous—not all that different from mainstream print media today.

Just how informal was the process? Consider, for example, that around 1887 John Tyndall wrote to Lord Rayleigh that since he was off to Switzerland he could not review the paper sent to him. On the other hand Poynting’s review of a paper by Reinold and Rucker, in 1893, where the reviewer did manage to write down their thoughts and not skip town is just two pages long and recommends the paper for publication.

Early formalisation

From the peer reports released by the Royal Society Archives it is unclear when the changes happened or why but by 1900 we see that peer review was no longer simply letter writing. A format was introduced, properly typeset with the Society masthead, and called upon reviewers to fill in specifically requested responses as part of the peer review process.

William Ramsay’s report from 1900 uses the new format. The review process was likely already confidential by this point but the new form makes that explicit. It also asks a few questions such as ‘whether ... it should be published in full or in part only, the part so to be published being indicated’ to which Ramsay answers simply “In full” (pictured below). There is a certain reductionism in the peer review here, making it shorter than the letters expected previously, so reviewers no longer noted their own summary of the paper, simply a word to allow publishing and sparse comments if it was worth their time.

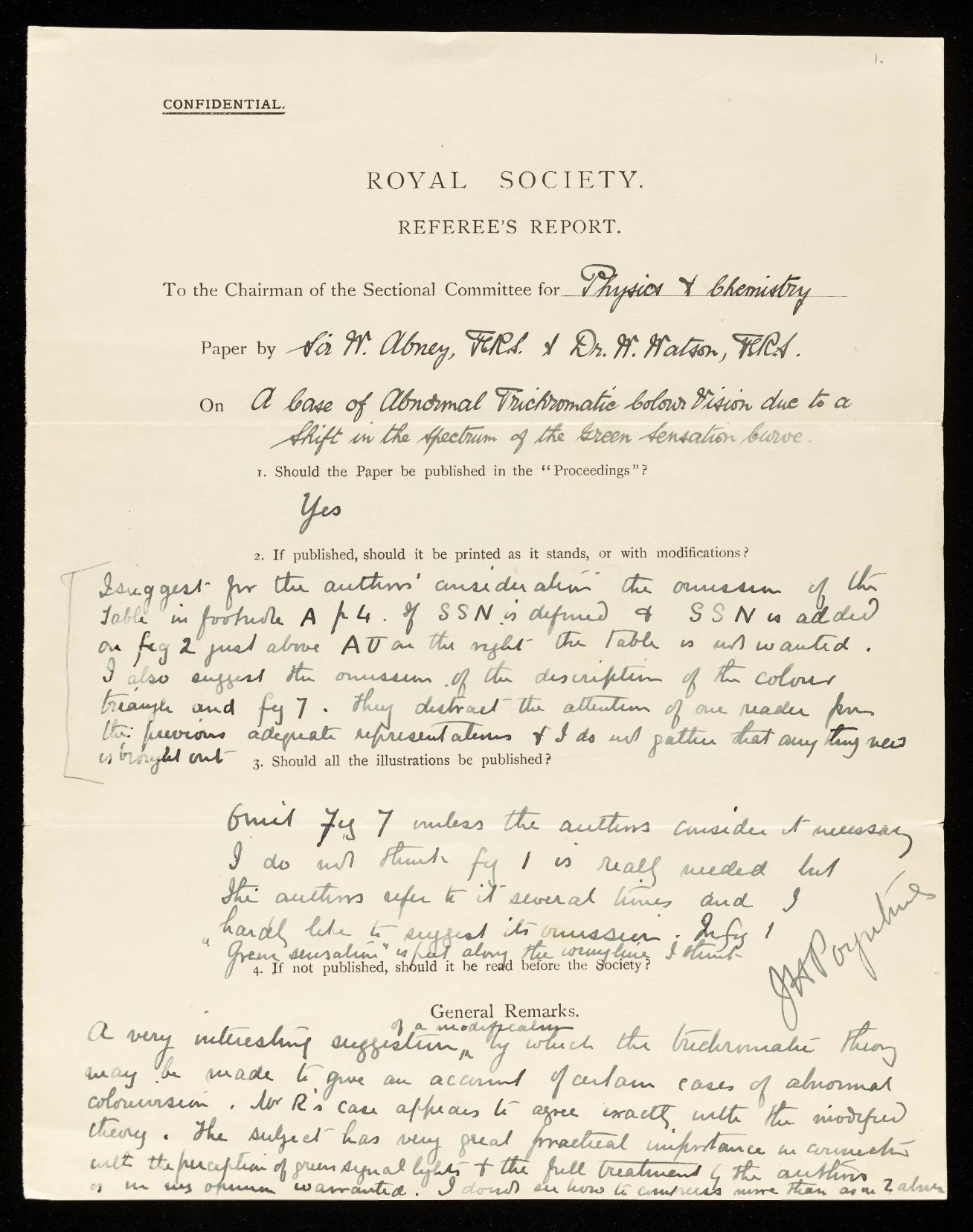

Interestingly, the format was changed less than a decade later. In Poynting’s 1913 review, for example (pictured below), we see an additional question: ‘Should illustrations be published?’ Unlike Ramsay’s one-word commentary, Poynting is more thorough, offering suggestions for modification and going out of his way to find additional space for his remarks, leaving himself barely enough space to sign. It becomes clear that by now the entire peer report is reduced to one sheet of paper.

Onwards and blind

If the physical process of the review was formalised, there were likely few unstated principles guiding it. For example, we take for granted today that the review is to be impartial and possibly blind (or double-blind) but even as late as the 1950s reviewers knew the authors and openly allowed themselves to be biased.

Writing to the Sectional Committee for physics, Harold Jeffrys notes about a paper by James Oldroyd that “Knowing the author, I have confidence that the analysis is correct.”

Interdisciplinary strains existed too, with the evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane rejecting a paper by Alan Turing in which Turing was attempting to demonstrate the use of mathematics and computational modelling from physics in the biological sciences. Haldane’s demand was that the mathematical portion was to be re-written in its entirety, but he did admit the topic itself was worth publishing.

All of this goes to show that scientific publishing has always been a human endeavour intended to protect the trustworthiness and reliability of science and has frequently erred and reformed itself, much like science itself. With the informal format seen until the 1900s, it appears that most pre-quantum and pre-relativistic physics was established with a highly informal peer review process (or none if you go far back enough). But with increasing collaboration and increasing complexity, the peer report had to keep up with the demands placed on it to ensure high standards of integrity and reliability.

Scientific publishing today is plagued by different problems but the emergence of the likes of arXiv point to a return to informal peer review as a means of continuing scientific growth even as formal review processes and corporatised publishing continues to take its own time.